Piloting gone wrong

This series highlights recent maritime accidents, detail their causes and highlight how intelligent systems could help prevent future incidents.

It is inspired by the fact that when I co-founded Shone, I learnt that most accidents happen due to human errors. Actually studies show that a staggering 96% of accidents are caused by human error.

Let’s take a look at an accident that happened in 2013 in the San Francisco Bay.

The allision of the Overseas Reymar with the Bay Bridge

What happened

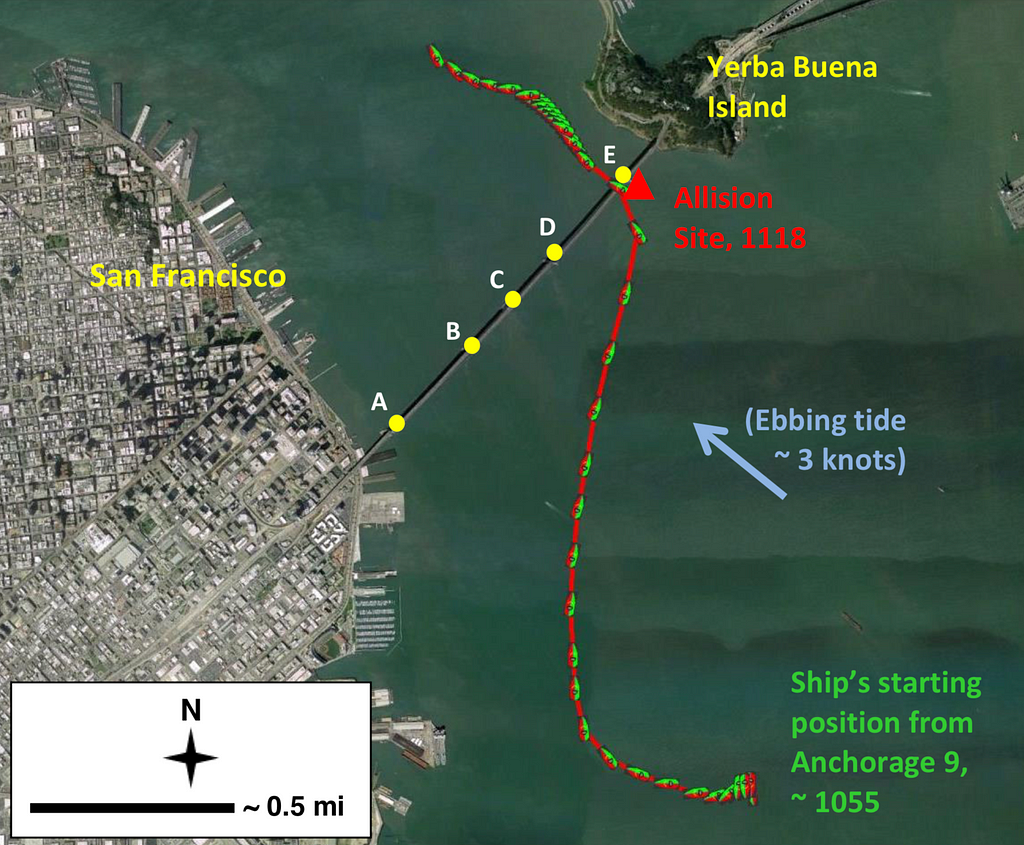

On January 7, 2013, at 11:18am, the 752-foot-long tanker Overseas Reymar allided with the fendering system of the San Francisco Bay Bridge’s Echo tower. The vessel was leaving the San Francisco Bay from anchorage after she had discharged her cargo of crude oil.

No one was injured and no pollution was reported. Damage to the vessel was estimated at $220,000, and the cost to repair the Echo tower’s fendering system was estimated at $1.4 million.

Soon after, on January 11, the ship was cleared to leave its anchorage and head to the drydock.

How did this happen

First, the day of the accident, visibility was poor as a thick fog was present. Visibility was estimated to be about one eighth of a mile near the bridge.

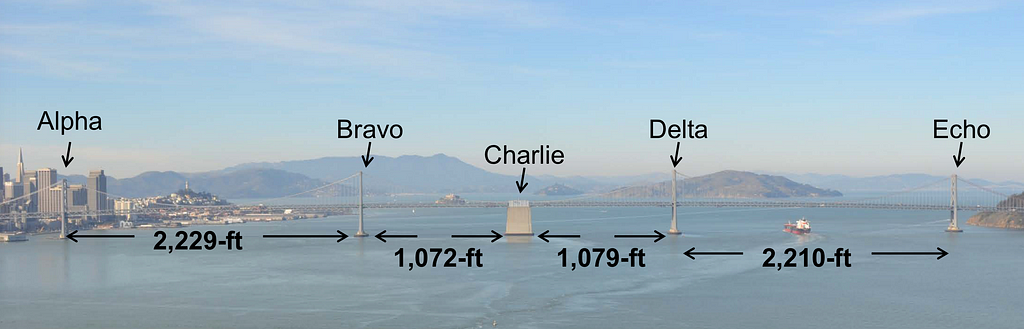

The pilot had initially planned to transit through the Charlie-Delta (CD) span of the Bay Bridge, even though the Delta-Echo (DE) span is more than twice larger. The reason invoked by the pilot was that he preferred doing always the same routes so that even in conditions of poor visibility his radar cues stay the same.

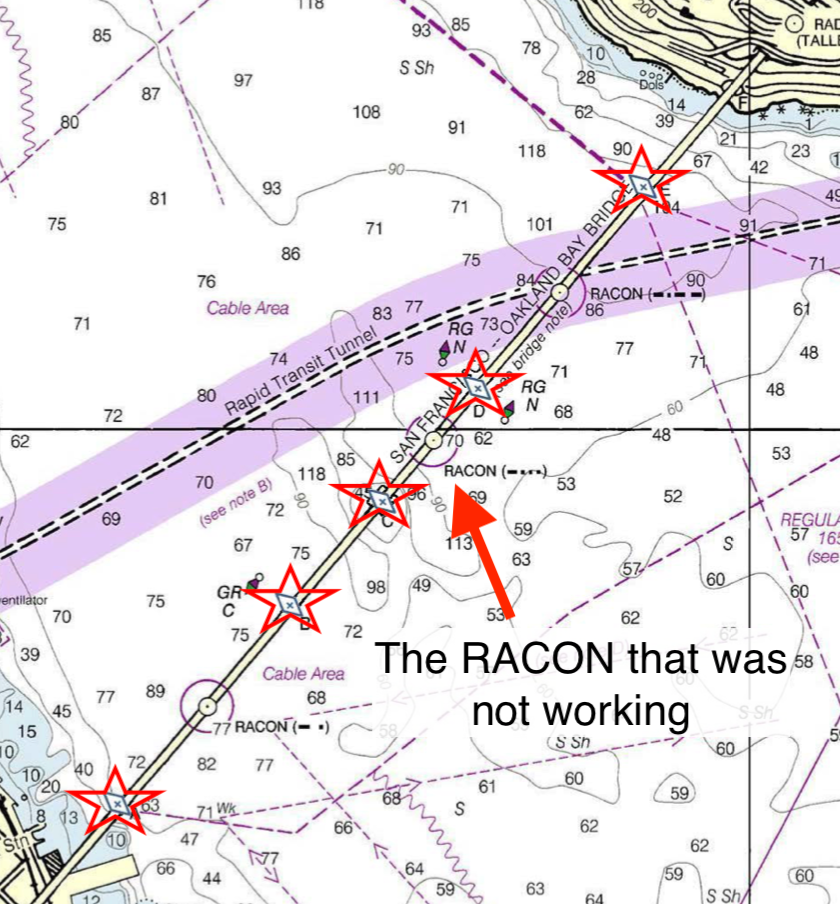

Digging into the NTSB report, it appears that the pilot changed his planned route at the last minute when he realized that a radar beacon (RACON) positioned on the Bay Bridge was not working properly and decided to go through the DE span.

Without visual sight of the bridge, the pilot proceeded to go through the DE span using RACON information. Three minutes before the allision, the pilot tried to align the ship for passage under the DE span. Thirty seconds before contact, Vessel Traffic Service contacted the pilot and informed him that the vessel was proceeding directly toward the Echo tower. This warning was not sufficient as the pilot thought that he was going under the bridge at the time it was given.

The probable cause for this allision was the pilot’s decision to alter course from the CD span to the DE span without sufficient time to avoid alliding with the bridge’s Echo tower, and the master’s failure to properly oversee the pilot by engaging in a phone conversation during a critical point in the transit.

NTSB report

The limitations of current instruments

The Overseas Reymar was equipped with modern navigation instruments such as Electronic Chart Display (ECDIS). Actually the NTSB noted that these tools should have been sufficient for an experienced pilot to safely guide the vessel under the CD span as he originally intended even without the RACON information.

But this clearly shows that current tools are not sufficient. The loss of the RACON information on the CD span was enough to throw off an experienced pilot and lead to an allision.

What are RACONs exactly?

RACONs are used in addition to aids to navigation (ATON) AIS transponders for static objects to help crews avoid obstacles such as bridges.

The RACON that was not working marks the midpoint of the CD span.

As mentioned previously, the day of the accident, visibility was extremely reduced (estimated to be 1/8th of a mile). In such weather conditions those markings are extremely useful to crews as they provide valuable information to help them guide the ships safely around obstacles.

Information overload in action

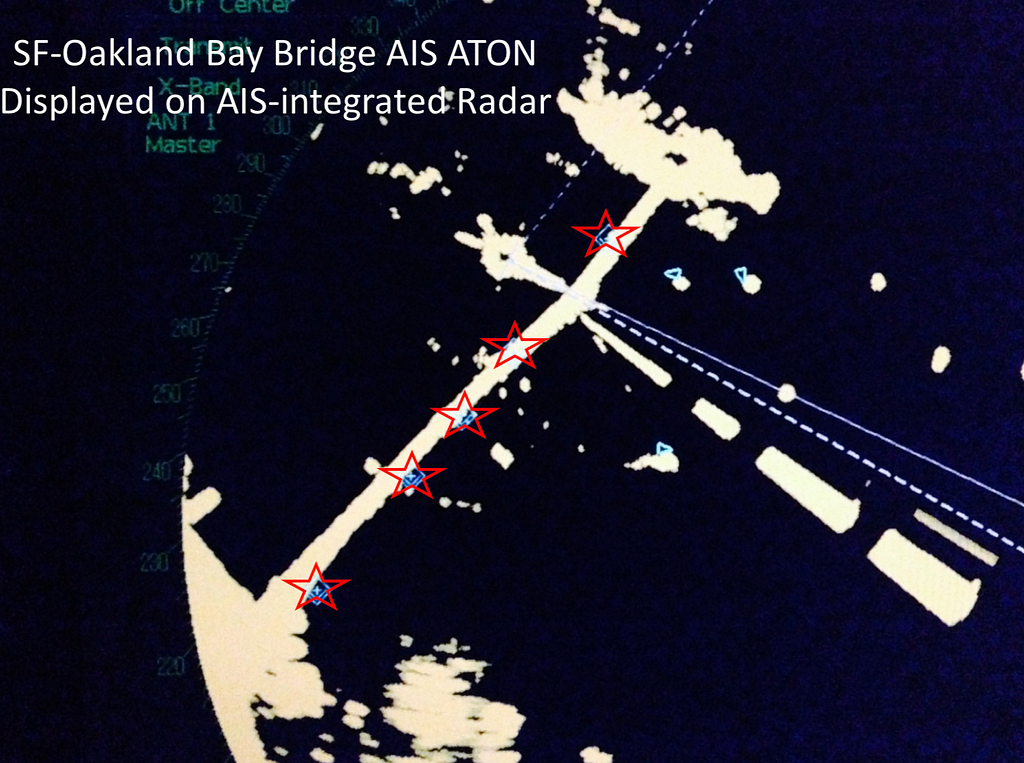

The main issue with the current systems is that they display layers of information on top of each other with no filtering between signal and noise, leaving the processing of that information to the navigation officers.

This is what the RACON and the ATON AIS from the Bay Bridge look like on a radar display. Notice in particular the following elements of this display:

- the ATON AIS (highlighted)

- the bridge’s radar echo

- the pillars’ echoes

- the RACON response

- AIS from nearby ships

- radar echoes of those nearby ships

- own ship’s radar echo and noise

There is no fusion of those different data sources, symbols just pile on top of each other and there is no semantic representation of what’s around the ship. And this is not even showing the chart overlay which can add dozens of additional symbols to this screen.

A speculation

Now looking at the screen above, I will speculate that the reason why the pilot really wanted the RACON echo is because it is the only clearly visible marking of where to go through the bridge. ATON AIS don’t jump out from the bridge echo, and pillars are hard to distinguish from noise.

Situational awareness: a way forward

At Shone, we believe that the way forward is to offer advanced situational awareness to seafarers to make them more efficient and prevent such accidents.

What lies ahead

Contrast the previous display with Waymo’s interface (nota: Waymo is Google’s self-driving car spinoff).

Information is represented semantically with a clear distinction between cars and pedestrians, the environment map, the planned trajectory and an explanation of what the car is doing in plain English.

Raw data is not information

There is no raw sensor data displayed as the system is trusted to have analyzed this data and extract the relevant information out of it. We want to apply the same philosophy to our system to unclutter the bridge’s displays and provide meaningful information that support directly the navigation officers’ decision-making.

We are currently working on these systems on actual cargo ships in operations and we are very excited to chat with crews, training centers and the regulator to understand how to better serve the maritime industry. Let’s make the future of shipping together!

If you have any thoughts or comments please feel free to contact me through our website!

Maritime accidents: Bay bridge, meet Overseas Reymar was originally published in Shone Blog on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.